Landing on Mars

An artist concept of the NASA's Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity rover examining a rock on Mars with a set of tools on the rover's arm, which can extend about 7 feet.

After five decades of sending robotic explorers to the surface of Mars, the journey is still fraught with dangers for every rover, probe and lander that humans launch. About two-thirds of all Mars missions have failed; many of them very publicly, bringing equal embarrassment to Russian, European and American space agencies.

So, when the Mars Science Laboratory launches from Cape Canaveral late this fall, the stakes will larger than ever. The project contains the next generation rover, Curiosity. NASA has invested years of work and over $2 billion into the project so far and been dogged by cost-overruns and missed deadlines.

Nonetheless, the agency that brought us Apollo and the Space Shuttle has had a string of recent successes on Mars. In the last decade, NASA has seen huge results from not only its two long lived rovers, but also the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and the Phoenix Lander.

That doesn't leave astronomers any less concerned for the fate of MSL. In 1999, the Mars Climate Orbiter was ripped to shreds as it hurtled through the planet’s atmosphere after engineers failed to convert their units from feet into meters. The Mars Polar Lander, which followed several months later, was also never heard from after its attempted landing.

MSL raises the stakes because it’s more complex than anything ever attempted on the surface of the red planet.

Looking to build on the success of the Mars Exploration Rovers Spirit and Opportunity, NASA decided to go big with Curiosity – the rover is five times larger than its predecessor rovers and will carry ten times the mass of scientific instruments– but that super-sizing means NASA had to reimagine how they would land the craft.

This image of the Mars rover family shows how the craft have increased in size since the Mars Pathfinder.

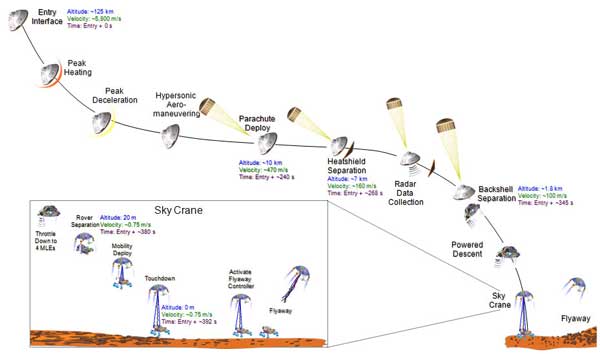

The task requires new landing technologies that will slow the craft from more than 13,000 MPH, allow it to survive the extreme heat of entering the atmosphere and then gently place it wheels-up on the planet’s surface.

Spirit and Opportunity, each about the size of riding lawn mower, used a system of parachutes and retrorockets to slow down from orbit and massive airbags inflated around the rover and it bounced its way across the surface at freeway speeds until it came to a complete stop.

Caption: Engineers prepare the heat shield for MSL at Lockheed Martin Space Systems in Denver this spring. The shield has a diameter of nearly 15 feet and is the largest ever built for a planetary mission.

When Curiosity reaches Mars, it will be folded up inside the largest heat shield ever used in space to protect it from the extreme friction of passing through the atmosphere. The heat shield will slow the craft down from its interplanetary travel speed to twice the speed of sound so that a supersonic parachute can be deployed

The heat shield then falls away and the 165 foot by 50 foot parachute unfurls while travelling at over 1,000 MPH. When the craft reaches a mile in above the surface, eight rockets begin to fire, slowing the fall even further. Meanwhile, the rover moves from its stowed position and its wheels deploy for landing.

In perhaps the most frightening of the landing stages, the rover is then lowered to the surface by the hovering platform via a system of cables that must be severed by small explosives for a “soft-landing.” The hovering craft must fly far enough away afterwards that its crash landing doesn’t impact the rover.

If any one of these carefully calculated and tested systems fail, the rover might suffer the same fate as many of its predecessors.

Descent

But if the mission succeeds, Curiousity is better equipped than any other Mars mission to unravel the planet’s secrets. Recent missions have shown that water was once abundant on the surface and water ice still might lie just beneath where our instruments can penetrate.

Curiousity will give further insights into those things, but also help unravel the largest mystery in the solar system: Alien life.

The rover will spend two Earth years trying to determine if Mars could have ever supported microbial life and if it still can.