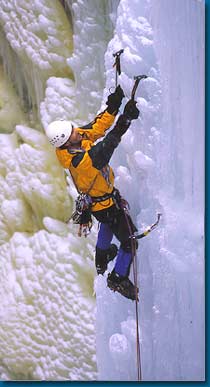

Steve Giddings

Steve Giddings on vertical ice.

(photo by Tyler Stableford)

Steve Giddings scaling an ice cliff.

(photo by Tyler Stableford)

As a theoretical physicist and an accomplished mountain climber, Giddings feels there are distinct parallels between his work and his hobby. “When you work on elementary particle physics or string theory, you’re appreciating nature on the subatomic level, and seeing the great beauty and intricacy in it,” explains Giddings. “And at the extra-galactic scale, the universe is a marvelous and fascinating thing. Mountaineering is a way of participating in that on a scale that is tangible to us as humans.”

Indeed, Giddings’ academic interests are about as intangible as physics gets these days. His primary research efforts currently include speculating on the fate of information cast into black holes, as well as the study of a new twist on string theory known as M-theory. It seems almost poetic that a physicist who contemplates string theory and gravity at its extreme limits would spend his free time dangling from cliffs in an extreme sport that sometimes seems to defy gravity.

In fact, Giddings is one of a surprising number of mountain climbing physicists. Recently, a photograph of Giddings scaling an ice cliff at Colorado’s Ouray Gorge illustrated a New York Times article that explored connections between physics and mountain climbing. While relatively few take the sport as seriously as Giddings, a number of his fellow physicists share a passion for technically challenging mountain climbing.

At the level that Giddings practices it, mountain climbing is an undeniably dangerous pastime - a handful of notable physicists have even lost their lives in the pursuit - but he points out that experience, careful planning, and good physical fitness reduce the risks. Nevertheless, you have to wonder why physicists in particular would be attracted to mountaineering. “We face these abstract and difficult challenges day after day after day. The number of times you can break through and do something that gives you a real sense of accomplishment is not so great,” says Giddings. “When you climb a mountain, you can look at it and see that it’s quite challenging. But you can put one foot after another and get to the top, usually, and get a feeling of accomplishment at a very visceral level. I think it’s good to get this sense of reward, which is more difficult to find in physics.”

Giddings inherited his love of both science and outdoor adventure from his father, a chemist and avid kayaker who led the first expedition to descend the headwaters of the Amazon (a subsequent trip down the Apurimac was later documented in Joe Kane's book Running the Amazon). Giddings also had a lot of opportunities to enjoy Utah’s geological splendor as a child growing up in Salt Lake City. After studying physics and mathematics as an undergraduate at the University of Utah, he managed to bear the comparatively tame landscape of Princeton long enough to earn a Ph.D. under superstring pioneer Ed Witten. Giddings is now a professor of physics at the University California at Santa Barbara. Although the landscape around Santa Barbara is not as dramatic as Utah, Giddings stays in shape between climbing trips by practicing on some of the local, relatively modest rock walls.

In the end, Giddings is clear about which of his two passions he most favors. “Physics is the higher priority. Climbing is a close second, but it is second. I take my physics very seriously,” says Giddings. “There’s a lot more I would have done in mountaineering if I felt like I could take more time away from physics. Doing good work in physics is very demanding, and you can only take so much time off in the mountains. That being said, though, for me they are both essential parts of a balanced life.”